A Quarry and a Community, Climate Change and the Irish Planning System.

A Quarry and a Community, Climate Change and the Irish Planning System.

On a ‘Storm Barra’ day in 2021, with an eerie grey in the

sky and debris across the roads, I drove through the community of Ballyshannon

in Kildare, trying to get a geographical and general sense of where a proposed

quarry was to happen. The storm caused disturbance around the country,

leaving debris in its wake but it felt also on the day like a presage of things to come,

a climate change occurrence that’s likely to be replicated many times over in

the future.

Yet what struck me here was the peace, and the sun filtering

through the clouds and casting light on the green fields. There were Christmas decorations in windows

but also a row of ‘Say no to the Quarry’ signs, showing a united opposition to

an application by Kilsaran concrete to develop another quarry in this rural

area.

|

| Field in Ballyshannon, C.Kelliher |

|

| Ballyshannon Field C.Kelliher |

|

| No to the Quarry Sign Ballyshannon, Kildare |

Ballyshannon is a small townland south of Kilcullen in

County Kildare and it was in October 2019 that the planning application was

submitted on behalf of Kilsaran Concrete (trading as Kilsaran Build) to Kildare

County Council. Even before this application arrived in the system, however,

people in the area were aware that something was coming down the line. Word of mouth had gotten round that the site at

Racefield, comprising of approx. 32 hectares had been bought by Kilsaran.

Residents of Ballyshannon and the wider community are no strangers to

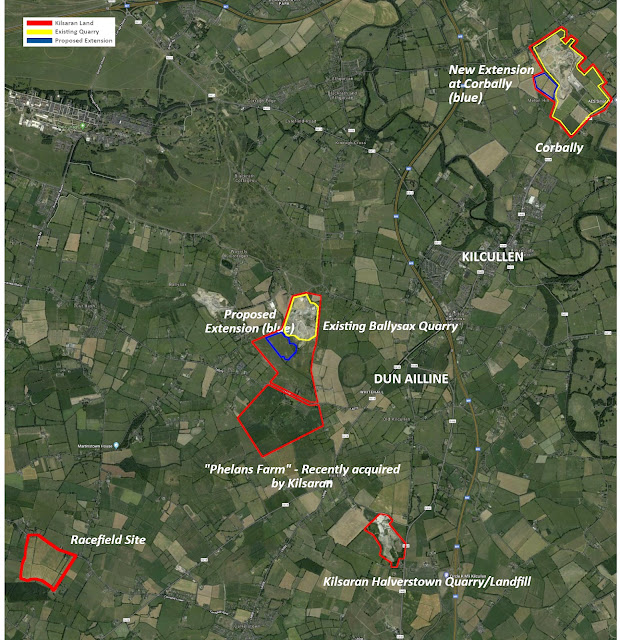

quarrying. As the map below indicates, Kilsaran already had active quarrying

sites in a number of locations, as well as obtaining land for future

development.

|

| Map of Kilsaran Quarries and Land |

The neighbourhood mobilised and held their first meeting on

14th October 2019 and a process began that would absorb and

galvanize a community for over two years.

From meetings to fundraisers, social media to submission clinics, all

the people involved have given freely of their time and energy to fight for

something they are deeply concerned about. In contrast, the resources available

to Kilsaran seem almost limitless by comparison. At first there was an early success as

Kildare County Council refused planning permission for the quarry. However, Kilsaran were quick to appeal this

decision. It seemed that Kilsaran had

very little regard for the people in the area, proceeding with an appeal

despite so much opposition locally.

|

| Public Meeting held by Ballyshannon Action Group |

Kilsaran can’t be blamed for doing what every company seeks, which is to increase profit. However it encapsulates an age old environmental issue, which is that many industries which prop up our economic systems are often in opposition to best environmental practice, creating pollution and damage to the natural world which we depend upon for food growing and for biodiversity.

This very topic arose at a Dáil debate in 2019, discussing both quarries and incinerators, highlighting ‘the severe and worsening impact on wildlife, biodiversity and ecosystems of some commercial activities which are known to be harmful or potentially harmful to the environment’ and asking that the government ‘ensure that the right to public participation, including early and open consultation in decision-making, is respected in the context of incineration and quarrying developments’.

It was felt by the Ballyshannon Action Group that preliminary consultation by Kilsaran was inadequate and that actions in extending other quarries in the area are an indication of a disregard for the needs of local people.

So why is the opposition to the quarry so fierce? People could be excused for seeing this as a type of nimbyism but the reality is a little bit more complex. The area, as mentioned previously, already has a number of quarries. The impact of quarrying on surrounding environments has been shown to be negative in many ways. Some of the areas of concern are dust, noise pollution, vibration, impact on biodiversity, the fact that well-established hedgerow is to be removed. The quarry could potentially impact the water quality in the area and affect the Curragh aquifer which was described in the Irish Times as ‘the largest and most important gravel aquifer (vast underground source of water) in Ireland.’

I spoke to Joanna Costello who has been active in the campaign to oppose the quarry. She highlighted some of the concerns the community have around the potential increased noise and pollution, the impact on the horse racing industry which is a key employer in the area and the danger of an additional 72 trucks (minimum) travelling along a small country road which is currently used by walkers and cyclists, as well as schoolchildren on their way to Ballyshannon National School. I asked how the campaigners felt when the An Bord Pleaneala decision came through and granted permission for the quarry. Joanna’s response was that the feeling was one of shock and I could sense that the impact of it was a big blow to all those who had put so much effort into raising awareness of all the issues.

However, she assured me that morale was still strong and that the community are very much still prepared to fight on. In fact they feel that they have no choice. They already have experience of Kilsaran requesting extensions on established quarries. The map at figure 3 shows the Corbally extension and also the proposed extension at the Ballysax site, so there is very little trust in the Kilsaran declaration of a 12 year period for the quarry. What has given some hope is support from the wider community and even further afield. The gofund me set up to raise money for the judicial review has gotten donations from near and far, with some people even setting up direct debits to assist the campaign.

Quarry Application Timeline:

|

Date |

Event |

|

03/10/2019 |

KCC received application for Kilsaran Quarry at Racefield – ref

19/1097 |

|

14/10/2019 |

1st meeting of Ballyshannon Action Group |

|

27/11/2019 |

Planning refusal given by KCC |

|

05/12/2019 |

Public Meeting Ballyshannon |

|

02/01/2020 |

Kilsaran lodge appeal with ABP |

|

16/01/2020 |

Public Meeting held by Ballyshannon Action Group |

|

25/01/2020 |

Submissions and Observations Clinic Ballyshannon Community Hall |

|

09/06/2021 |

ABP granted permission with conditions |

|

16/07/2021 |

Public Meeting at Ballyshannon National School |

|

08/08/2021 |

Procedures begun for Judicial Review Application |

|

07/12/2021 |

Judicial Review Application Adjournment |

|

25/01/2022 |

Judicial Review Application adjourned to this date |

From previous research, the environmental impacts of quarrying are well known. It is important to stress that it’s not possible to assess exactly what the environmental damage will be from the proposed quarry at Racefield, as factors such as geographical location, wind and company mitigation measures put in place by Kilsaran will all have an impact on the final result. However, if we take dust as one example, there is the potential effect on human health, on biodiversity and on the visible appearance of the environment close to the quarry site. Again, the effects of dust and the quantities of damaging particulates is dependent on distance from quarry, methods used, wind and type of quarry, as well as quality of haul paths. Limestone quarries can have an effect on lichens and botanical material in the surrounding areas. A 2018 study on dust from quarries concluded that: ‘crushing has the most significant effect on dust concentration caused by quarries’ and ‘Quarries produce mainly coarse particles, which is supported by all studies measuring fine and coarse particle concentration.’

I spoke also to Eoin Houlihan, a resident of Kilcullen, the nearby town through which the Kilsaran trucks move on a daily basis, from quarry to quarry. Like many other Kilcullen residents, Eoin is concerned about the prospect of an increased volume of traffic and the toxic fumes emitted. He spoke about the speed of the trucks and the dangers on the road for drivers, but also about the difficulty of trying to encourage walking and cycling in the community, when the presence of these trucks is such a huge deterrent. Unofficial counts have suggested that the frequency of trucks is currently 30 per hour which reflects current quarry activity without the additional material from a new quarry. This seems to belie the assurances given to Eoin by Kilsaran representatives, who maintained that truck volume would not increase with the new development and that private contractors wouldn’t be used. Like Joanna, Eoin has felt demoralised but is not ready to give up the fight. The imbalance of resources makes it difficult but the passion to oppose the development is still strong. Eoin also pointed out the proximity of Dún Ailinne which is ‘currently being assessed for consideration as a UNESCO World Heritage site’ (Details here)

|

| Dún Ailinne Ancient Site |

What is abundantly clear is that a quarry in the area will fundamentally affect the life and environment in the surrounds. And this was explicitly outlined in both the Kildare County Council refusal and also in the report issued by the ABP Inspector.

Some of the reasons outlined for the initial refusal from Kildare County Council (available here) are poor quality road network and insufficent ability to put safety measures in place, ‘lack of adequate baseline information presented in respect of the sensitive receptors (referring to the proximity of residential dwellings). The Inspector’s report also refers to the fact that:

‘the applicant has not demonstrated to the satisfaction of the Planning Authority that the qualifying interests of the European Site, the River Barrow and the River Nore SAC, site code 002162, will not be adversely affected by the proposed development.’

The An Bord Pleaneala Inspector’s report which can be viewed here, states that:

‘the proposed project would have unacceptable direct or indirect impacts on the environment as it relates to population and human health, and in particular residential amenity, noise, roads and traffic. There are also further potential significant impacts arising in relation to the extensive removal of internal hedgerows and associated impacts on bats, badgers and breeding birds, surface waters and archaeology and cultural heritage.’

Therefore, in light of the 229 objections to the original application, the Kildare County Council refusal of planning permission and the ABP Inspector’s report, it is even more difficult to understand how this development was given the green light. And it certainly begs the question as to why this decision was made. The people I spoke to were baffled and felt that a lack of transparency was at play. Certainly the role of An Bord Pleaneala seems to play a part in many poor environmental decisions, some of which appear to be in direct opposition to carbon reduction targets laid out in the Irish Climate Action Plan 2021.

One such decision was the granting of permission for construction of a cheese manufacturing plant in Kilkenny, a decision which was challenged by An Taisce but then upheld by the High Court. Given that agricultural emissions were responsible for 37% of Ireland’s total greenhouse gas emissions in 2020, according to the EPA, the decision appears to be contrary to tackling those very emissions.

Another very recent decision, referred to in this article,

is the approval of the Galway Ring Road and the negative impact on climate and

emissions which is referred to in the ABP report here

–

‘That the proposed development would be likely to have a

significant adverse impact on carbon emissions and climate.’

It is undoubtedly true that the task of balancing economic

and environmental requirements within a political and legal system, is not a

straightforward process. However, given that Ireland’s emissions are not on any

meaningful downward trajectory, the role of statutory agencies is crucial. Within that system, it is also essential that

meaningful consultation takes place.

When I spoke to Dr. Liz Cullen, a local resident, this

subject was raised and she expressed her disillusion with the process, saying

‘What does democracy mean? You would question the whole democratic process.

What is influencing decision making?’ She feels, similar to others I spoke to, that

there is a lack of transparency and a sense that decision making is happening

behind closed doors.

Dr. Cullen very aptly summarised the perception of

inequalities in the system by saying that ‘people will pay the price although

Kilsaran will make the profit.’

A critique of planning law from a Marxist perspective, done in

2011 by Linda Fox-Rogers et al, highlights this very point and ‘demonstrates

how recent legislative change in the Republic of Ireland has been designed

specifically to reduce public participation in the planning process’, and ‘is a

clear attempt to reduce the democratic nature of the planning process, thereby

consolidating and prioritising the interests of private capital over those of

the general population.’

From the recent EPA/Yale study on attitudes to climate

change in Ireland, 79% of Irish people say climate change should be either a

‘very high’ or ‘high’ priority for the Government of Ireland.

With this in mind, it seems contradictory in light of the Government impetus to tackle climate change that it is often devolved to ordinary people to fight for environmental justice and protection of the area around them.

‘Poor decisions made today that do not adequately account for ongoing and projected climate changes are locking in future vulnerabilities. The Council reiterates the essential importance of an integrated, multidisciplinary, long term systemic approach, within public policy making, towards adaptation and mitigation as a means of combating climate change and building resilience.’

Above is a quote from the recent Climate Council of Ireland Report. It seems that An Bord Pleaneála continues to make ‘poor decisions’ when it comes to protecting biodiversity and reducing carbon emissions and one wonders when the integrated approach will begin?

In any case, it may be too late for the residents of Ballyshannon and surrounds, who, if the scheduled application to go to judicial review is not successful, will have their lives severely impacted by the noise, vibration and air pollution of quarrying activity, as well as the damage to rivers and biodiversity that is likely to ensue.

(Note: This article was previously submitted as an academic assignment as part of my Master's in Climate Change, Policy, Media & Society in DCU. Full academic references were supplied as part of this and the reference list is available on request.)

References:

Interviewees:

Joanna Costello, 30th November, 2021.

Eoin Houlihan, 4th December, 2021.

Dr. Liz Cullen, 12th December, 2021.

Special thanks to Brian Byrne of the Kilcullen Diary, who

provided assistance and information and has extensively covered this issue in

the Kilcullen Diary online.

All images, unless otherwise indicated, are courtesy of

Ballyshannon Action Group.